Why we need to ask tough questions about gangs and crime among young Muslim men

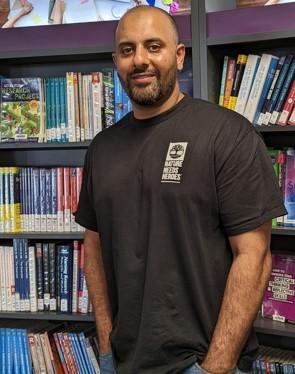

Dr Mohammed Qasim is not your typical academic - he has spent years following gangs and drug dealers in order to better understand the causes of crime.

He has now joined the University of Bradford as a visiting research fellow and will lend his considerable expertise to students.

His research has been covered by outlets such as The Guardian, The Telegraph, Vice and the BBC; he is author of Young, Muslim and criminal: Experiences, Identities and Pathways into Crime (2018, Policy Press), and is in the process of writing and contributing to three more books focusing on issues such as crime, identity, in equality and the social history of the UK’s Pakistani community.

He says: “I think it’s going to benefit criminology students to hear real life accounts of what it’s like to research gangs. The issues I focus on in my research are race and inequality, identity and opportunity. There are many negative associations with young British Muslim men, such as links to terrorism and gangs. When I look at these topics from a research perspective, it’s not a case of exposing them for the sake of it, it’s about highlighting issues that will ultimately benefit society.

“We need to understand why such a large number of British born Pakistani Muslims end up being involved in crime. Systemic racism plays a part but there are a whole range of other issues to consider.”

Cultural divisions

Born and raised in Bradford, the third of four children, Dr Qasim grew up in Manningham and attended Belle Vue Boys School, leaving around the time of the Bradford Riots (2001), which greatly influenced his career path. He witnessed first hand the cultural divisions that led to what turned out to be an era-defining outburst of social unrest, the effects of which one could argue are still being felt today.

“I grew up in Bradford, I was raised here. That’s why I wanted to come back. I went to school with kids who took part in the riots. These were young people who entered the criminal world, many of them ended up with criminal records, which then had a knock-on effect in terms of their employability. The other thing the riots did is de-incentivise investment in Bradford. I became interested in that. Most of my research for Young, Muslim and criminal was done here in Bradford. These are real issues and I think it’s important to discuss them, and not brush them aside.

“We also need to accept that we cannot imprison our way out of crime. The real issues that make young Muslim men turn to criminality are the reasons why anybody turns to criminality: you're living in deprived communities, your education levels are appalling, job opportunities are limited, institutional racism limits opportunities, a culture of crime starts to escalate in the neighbourhood, your role models become people who are drug dealers. You see that it's easy to become a drug dealer, and it's difficult to find a job".

Gang culture

He cites UK prison population statistics published by the Ministry of Justice in October 2021 which state Muslims now make up 18 percent of the prison population, despite comprising around five percent of the national population. The same document states: “the BAME population is overrepresented within the prison population” with 28% identifying as BAME, compared to 13% nationally.”

Indeed, the question of identity features strongly in Dr Qasim’s research.

“If you look at humans, there’s a need for belonging. Some people have the opportunity to find stable groups - and these might be things like playing snooker or pool once a week, for example. But there are others, and particularly young people, who do not get into stable groups, and these are often the ones that find gangs and street culture appealing.

“Being part of a gang brings with it a certain amount of credibility, and certainly in some deprived communities, ‘street cred’ carries a lot of weight.”

Dr Qasim was the first person in his family to attend university, gaining a degree, Master’s and PhD in criminology from Swansea, in addition to a PGCE, before moving into academia, teaching first at Swansea and more recently Leeds Beckett and London School of Economics. Now a father-of-three and a judo instructor (he has practised martial arts for over 20 years), he says he is keen for his research to make a difference in improving people’s lives.

For example, he would like to see a much more comprehensive approach to support services, particularly for young people, to help steer them away from criminality, whether it's gangs, drugs or something else.

Professor Peter Mitchell, head of the School of Social Sciences, says: “Dr Qasim’s research into cultural and community issues is both fascinating and of great importance if we are to gain a deeper understanding of some of the root causes of crime and issues relating to race and identity. We are fortunate to have someone of his calibre contributing to the learning experience of our students, and we wholeheartedly welcome him to the university.”

Dr Qasim adds: “Working with gangs for so many years… gaining their trust is both difficult and dangerous, because at the end of the day, I am studying them, I am looking at how they operate and the reasons why they do what they do. Understanding that is crucial if we want to bring about any meaningful change that improves not just those communities but society as a whole, and that’s why I’m so passionate about my work.”